| Drug Name: | Diazepam (generic Valium) |

|---|---|

| Tablet Strength: | 10 mg |

| Best Price: | $167.95 (Per Pill $3.49) |

| Where to buy | OnlinePharmacy |

Since its introduction in the early 1960s, diazepam has held a central place in the pharmacological arsenal of neurologists, psychiatrists, and rehabilitation specialists. As one of the earliest benzodiazepines to reach widespread clinical use, it rapidly earned a reputation for its broad therapeutic spectrum, favorable safety profile, and unmatched versatility. Today, over six decades later, diazepam continues to be prescribed in a wide range of settings — from acute emergency care to long-term neurorehabilitation — cementing its status as a proven standard in modern medicine.

Diazepam is classified pharmacologically as a long-acting benzodiazepine with potent anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, muscle relaxant, and amnestic effects. This unique combination of properties allows it to address both central and peripheral neurological dysfunctions, which are commonly observed in patients with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, brain trauma, or post-stroke syndromes. Its mechanism of action, involving modulation of the GABAergic system, offers reliable symptom control in both acute and chronic scenarios, while maintaining a relatively low risk of severe adverse effects when used responsibly.

In rehabilitative care, diazepam plays a key supportive role in reducing barriers to speech production, physical mobility, and patient participation in structured therapy programs. By decreasing pathological muscle tone, alleviating anxiety, and controlling episodic seizure activity, diazepam enhances a patient’s capacity to engage in physical, occupational, and speech-language therapy. These benefits are particularly evident in the management of spastic dysarthria, dysphagia, and neurogenic communication impairments.

Its long clinical history has allowed for extensive data collection on safety, dosage adjustment, pharmacokinetics, and interaction profiles, making it a thoroughly characterized and predictable agent. While newer drugs have emerged with more targeted or selective mechanisms, few offer the same combination of broad neurological applicability and cost-effectiveness. This makes diazepam a mainstay not only in hospital formularies, but also in outpatient settings where consistency and familiarity are valued by clinicians.

In many parts of the world, diazepam is included in essential medicine lists and national treatment protocols, particularly for managing spasticity, anxiety, and seizure clusters in vulnerable populations. Its role in pediatric neurorehabilitation is especially well-established, with applications ranging from managing cerebral palsy to facilitating procedural sedation during therapy. In geriatrics, it is used more cautiously but still plays a role in palliative and supportive care settings.

Diazepam remains an indispensable medication for neurologically compromised individuals requiring complex rehabilitative care. Its robust therapeutic profile, decades-long track record, and multimodal benefits make it more than just a sedative — it is a functional enhancer within the larger context of patient-centered recovery. For these reasons, diazepam deserves continued recognition and thoughtful integration into individualized neurotherapeutic regimens.

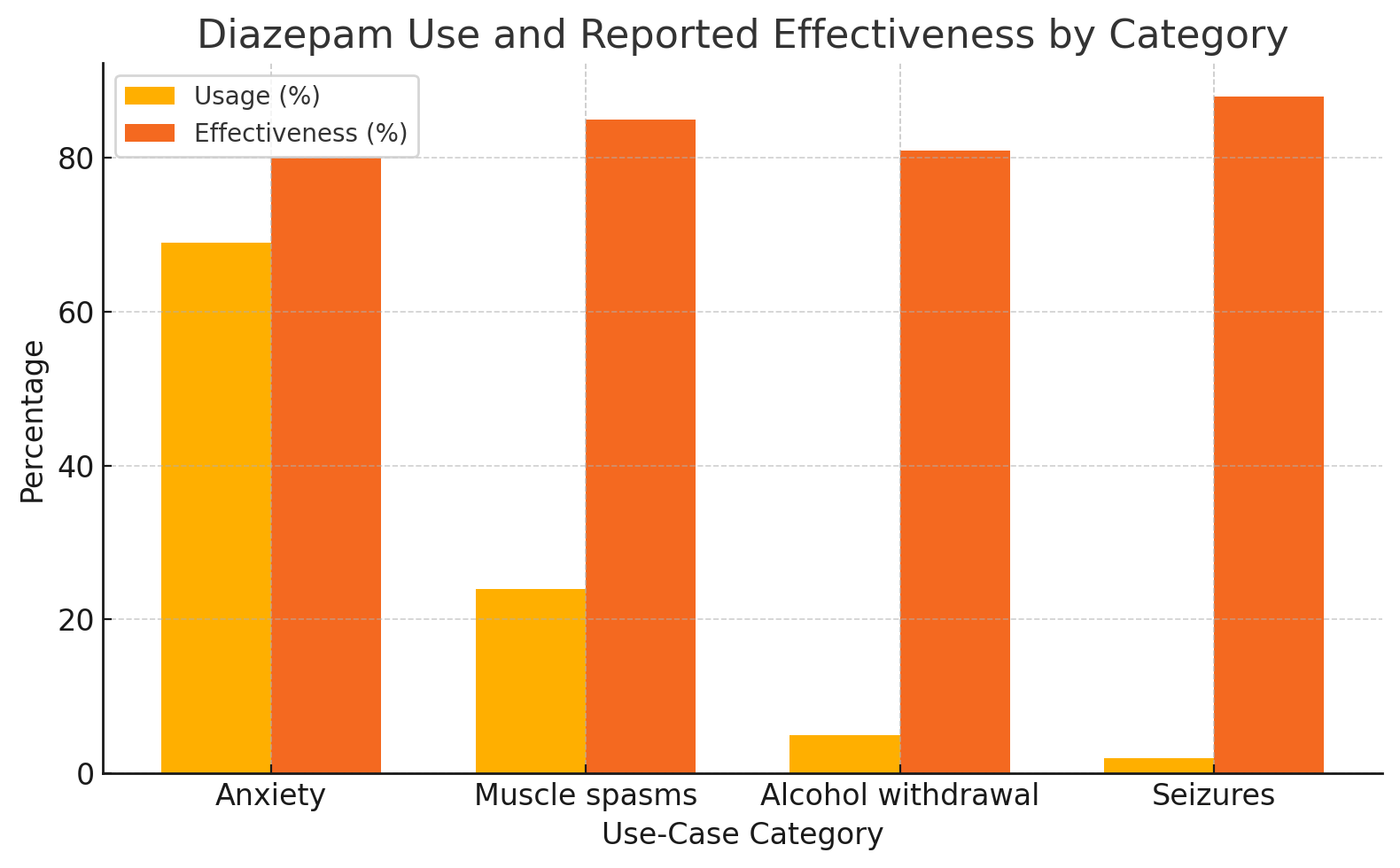

Diazepam is prescribed for a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions, including anxiety disorders, muscle spasms, alcohol withdrawal symptoms, and seizures. Its mechanism of action allows it to address both acute and chronic dysfunctions of the central nervous system. The data below summarize key areas of clinical use, showing how diazepam is distributed across major therapeutic categories and how users rate its effectiveness in each context.

| Use-Case Category | Reported Usage (%) | Reported Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 69% | 80% |

| Muscle spasms | 24% | 85% |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 5% | 81% |

| Seizures | 2% | 88% |

Based on user-reported data, diazepam demonstrates high effectiveness across all listed indications. Anxiety accounts for the majority of reported use, followed by musculoskeletal and withdrawal-related cases. Despite being less frequently used for seizures, diazepam receives the highest effectiveness rating in that category, reflecting its acute anticonvulsant properties. This distribution highlights its multi-functional clinical role and consistent therapeutic outcomes.

Diazepam belongs to the class of long-acting benzodiazepines and exerts its pharmacological effects by modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter pathway in the central nervous system. Its core mechanism involves enhancing GABAergic transmission via positive allosteric modulation of GABA-A receptors. By binding to a specific benzodiazepine site on these receptors, diazepam increases the frequency of chloride channel openings in response to GABA, leading to neuronal hyperpolarization and reduced excitability.

This inhibition results in a wide range of clinically beneficial effects: anxiolysis, sedation, muscle relaxation, anticonvulsant activity, and amnesia. These properties account for diazepam’s ability to control epileptic seizures, reduce anxiety-related symptoms, suppress spastic muscle contractions, and facilitate preoperative sedation or procedural tolerance in both medical and rehabilitative contexts. The rapid onset of action and reliable efficacy have contributed to its sustained inclusion in emergency protocols and essential medicine lists worldwide.

After oral administration, diazepam is rapidly absorbed, with bioavailability approaching 100%. Peak plasma concentrations are typically achieved within 30 to 90 minutes. The drug is highly lipophilic, enabling it to cross the blood-brain barrier efficiently and exert central nervous system effects. Diazepam is metabolized hepatically via cytochrome P450 enzymes, especially CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, into active metabolites such as desmethyldiazepam, temazepam, and oxazepam, all of which contribute to its prolonged duration of action.

Its elimination half-life ranges from 20 to 50 hours in most individuals but can be significantly longer in the elderly or those with hepatic impairment due to reduced metabolic clearance and accumulation of active metabolites. This long half-life supports sustained therapeutic effects, especially in the context of chronic muscle spasticity or generalized anxiety, but it also necessitates careful dose management to avoid drug accumulation and next-day drowsiness.

In the context of neurorehabilitation and speech-language pathology, the pharmacokinetic stability of diazepam is advantageous for maintaining consistent neuromotor tone modulation across therapy sessions. A single well-timed dose can provide coverage during a multi-hour therapy block, reducing the need for repeated administration. This is especially useful in managing conditions like spastic dysarthria or persistent pharyngeal hypertonia, where even small fluctuations in tone can impede therapy progress.

Pharmacodynamically, diazepam has a dose-dependent profile. At lower doses, it produces anxiolytic and muscle-relaxant effects with minimal sedation. At moderate to high doses, sedation becomes more prominent, along with significant impairment of short-term memory and coordination. This profile allows for flexible titration depending on the therapeutic goal—whether the aim is to suppress seizure activity, reduce anxiety interfering with communication, or temporarily diminish spasticity in preparation for physical or speech therapy.

Tolerance to some effects of diazepam, particularly the sedative and muscle-relaxant components, may develop with prolonged use. However, its anxiolytic and anticonvulsant actions tend to remain stable with appropriate dosing schedules. Understanding these dynamics is essential for clinicians to maximize therapeutic gain while minimizing risks, especially when diazepam is used as an adjunct to complex rehabilitative programs.

Diazepam’s pharmacological versatility arises from its reliable absorption, prolonged duration of action, active metabolites, and powerful enhancement of GABA-mediated inhibition. These characteristics make it uniquely suited for both acute symptom control and sustained neuromuscular modulation in neurological recovery and speech rehabilitation. However, due to its potency and long half-life, clinical vigilance and interdisciplinary coordination are essential to ensure optimal therapeutic outcomes.

As healthcare continues to evolve digitally, more individuals are seeking flexible and discreet ways to access medications, including diazepam. Whether due to mobility issues, limited local availability, or a preference for privacy, online purchasing has become a viable and increasingly common method for obtaining prescription treatments. However, responsible access depends on being well-informed. This section outlines key points for patients considering online options for acquiring diazepam, focusing on how to navigate the process efficiently, confidently, and with personal safety in mind.

Diazepam is widely used in both acute and long-term care for conditions involving muscle spasms, seizures, anxiety, and motor control disorders. With growing demand for remote care solutions, online platforms have adapted to include not only informational content but also consultation services, prescription fulfillment, and direct-to-door delivery options. These services often streamline access for individuals who would otherwise face delays, long travel, or difficulty coordinating care through traditional clinical settings.

Online pharmacies and telehealth services vary in scope and structure. Some offer direct access to consultations with licensed medical professionals who can assess a patient’s condition and prescribe treatment remotely. Others are structured for patients who already have prescriptions and simply need a convenient way to have them filled and shipped. Understanding what type of platform you're using helps clarify expectations and ensures smoother coordination of care.

Ordering diazepam online can be especially helpful in scenarios where access to local pharmacies is limited due to location, disability, or temporary unavailability. Patients undergoing long-term therapy may also prefer to manage refills digitally, reducing the need for in-person interactions and maintaining consistent access during travel, relocation, or scheduling conflicts. For those receiving care from multiple specialists, online services can also help consolidate medication routines and improve adherence by offering automatic refill options and reminders.

In rehabilitation settings, individuals with neurological disorders or speech impairments often benefit from simplified routines. Online ordering allows patients, caregivers, or family members to coordinate delivery without disrupting therapy schedules. In such cases, the reliability and predictability of delivery play an important role in maintaining continuity of care.

Choosing a service that aligns with your needs involves more than convenience. Reliable providers make the process transparent from start to finish. This includes clearly explaining how prescriptions are reviewed or processed, what delivery options are available, and how questions or concerns will be handled. Access to professional support—such as a medical advisor or pharmacist—is often a valuable feature, especially when initiating therapy or adjusting dosage.

Platforms that focus on long-term therapeutic support often provide educational resources, medication tracking tools, and responsive customer assistance. Many also offer user accounts where patients can view their prescription history, manage orders, and set refill schedules. When evaluating a service, it helps to review user interface clarity, support availability, and the range of medications offered—all of which contribute to a better overall experience.

For many patients, privacy is a top consideration—particularly when it comes to medications used in mental health, neurology, or speech therapy. Online ordering can help preserve discretion by minimizing in-person conversations and providing neutral, unbranded packaging upon delivery. Most services also offer confidential communication channels, allowing users to ask sensitive questions or request specific instructions without exposure to a public setting.

Clear and consistent communication is another important factor. A provider should offer email or chat support, order tracking, and timely notifications. Whether managing a long-term prescription or trying diazepam as a new treatment option, patients benefit greatly from platforms that keep them informed at every stage—from order confirmation to delivery updates. When digital care works smoothly, it helps reduce stress and allows patients to focus on recovery and rehabilitation.

Ordering diazepam online is a practical solution for many individuals receiving treatment for neurological or rehabilitative conditions. With thoughtful selection and attention to communication, patients can experience a process that is safe, efficient, and centered on their needs. When integrated into a broader therapeutic plan, digital access becomes a meaningful component of continuity in care.

Diazepam has a well-established presence in the management of numerous neurological and psychiatric conditions. Its pharmacodynamic profile, which includes anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and muscle-relaxant properties, allows for broad applicability in both acute and chronic care settings. In neurology, diazepam is used for treating seizure disorders, acute dystonic reactions, spasticity related to upper motor neuron lesions, and muscle rigidity seen in conditions such as multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury. In psychiatry, it plays a critical role in the short-term management of anxiety disorders, panic attacks, and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

One of the most important uses of diazepam is in the treatment of epilepsy. It is considered a first-line agent for terminating active seizures, especially in the context of status epilepticus or prolonged convulsive episodes. It can be administered orally, rectally, or intravenously depending on the urgency and clinical setting. Rectal diazepam formulations are frequently used in home care for children with seizure disorders, allowing caregivers to intervene early and prevent hospital admissions. Its rapid onset of action and sustained effects make it suitable for both emergency and transitional seizure control before long-term antiepileptic therapy is optimized.

In the context of muscle disorders, diazepam is often used for reducing painful spasticity caused by brain or spinal injuries. It decreases hyperactive stretch reflexes, facilitating more natural movement and improving patient comfort. This benefit is particularly relevant in stroke rehabilitation, where focal or generalized spasticity may interfere with gait, limb positioning, and fine motor activities. In such cases, diazepam is sometimes used as a preparatory agent before physical or occupational therapy sessions to increase range of motion and reduce resistance.

In psychiatric applications, diazepam is commonly prescribed for the short-term relief of severe anxiety symptoms. It helps alleviate excessive nervous system arousal, improve sleep, and reduce psychosomatic symptoms such as chest tightness or restlessness. It is often used in acute psychiatric settings for agitation, panic attacks, or during the early phases of antidepressant titration, where temporary anxiolytic support is required. Additionally, diazepam has long been employed in managing alcohol withdrawal syndrome. It reduces the risk of withdrawal seizures, helps stabilize vital signs, and eases irritability or tremor during detoxification.

Although not a first-line therapy for chronic psychiatric conditions, diazepam remains a valuable agent in transitional and supportive contexts. Its rapid onset and high tolerability make it useful during diagnostic evaluations or periods of clinical instability. However, the risk of tolerance and dependence necessitates careful patient selection and time-limited use. The goal is to use diazepam as a stabilizing bridge while longer-acting or disease-modifying therapies take effect.

The role of diazepam in neurorehabilitation has grown steadily as clinicians recognize its ability to modulate both neuromuscular tone and emotional arousal, two factors that significantly affect therapy outcomes. In patients with central nervous system injuries, such as stroke, cerebral palsy, or traumatic brain injury, diazepam can help reduce resistance to movement, diminish involuntary muscle activity, and alleviate distress that interferes with participation in therapy. These effects are particularly relevant in the context of speech-language rehabilitation, where spasticity, anxiety, and motor instability often complicate recovery.

One of the primary speech-related applications of diazepam is in the management of spastic dysarthria, a condition characterized by slowed, strained, and effortful speech due to increased tone in the orofacial musculature. In cases where hypertonicity prevents accurate articulation, brief pre-session administration of diazepam may relax the jaw, tongue, and laryngeal structures, allowing patients to practice phonation and prosody with greater freedom. This strategy is especially useful during intensive rehabilitation periods, such as inpatient recovery after stroke or in specialized cerebral palsy programs.

In swallowing therapy (dysphagia rehabilitation), diazepam may improve outcomes by reducing pharyngeal and esophageal spasm. When applied judiciously, it enhances the coordination of muscle groups involved in deglutition, thereby decreasing aspiration risk and improving the efficiency of nutritional intake. These benefits support not only speech-language outcomes but also overall patient safety and functional independence. Clinical teams may use diazepam as an intermittent aid for therapy sessions, rather than as a routine medication, to avoid sedation or cognitive blunting.

Beyond its muscular effects, diazepam also supports cognitive-emotional readiness. Many patients undergoing speech therapy experience frustration, anxiety, or resistance, especially when recovery is slow or marked by setbacks. In select cases, low-dose diazepam can reduce this psychological burden, allowing greater engagement and receptivity to instruction. This is especially beneficial in patients with limited insight or those experiencing emotional dysregulation as part of their neurological condition.

Importantly, the use of diazepam in speech and neurorehabilitation is highly individualized. Not all patients benefit equally, and inappropriate use may impair attention, alertness, or memory. A collaborative approach between neurologists, physiatrists, and speech-language pathologists ensures that the timing, dosage, and duration of diazepam administration align with therapeutic goals. When integrated carefully, it acts as a supportive tool that enables the physical and psychological readiness needed for meaningful communication recovery.

Diazepam is one of the few centrally acting agents that has well-documented usage in both pediatric and geriatric populations. However, age-specific physiological differences require careful dose adjustment, safety monitoring, and therapeutic planning. In children, diazepam is commonly used for conditions such as febrile seizures, spasticity in cerebral palsy, and procedural anxiety. In older adults, it may be prescribed for muscle spasms, sleep disturbances, or agitation, but its use is limited due to increased sensitivity and slower metabolic clearance.

In pediatric neurology, diazepam is especially valued for its rapid anticonvulsant effect. Rectal and intranasal formulations allow caregivers to administer emergency treatment at home during prolonged seizures, reducing the need for hospital admission. Oral diazepam may also be employed in managing nighttime spasticity in children with neuromotor disorders, improving sleep and enabling better participation in daytime therapy. However, due to its sedative potential, dosing must be minimal and based on body weight. Clinicians often begin with the lowest effective dose and monitor closely for drowsiness, paradoxical reactions, or behavioral changes.

Behavioral side effects such as irritability, restlessness, or emotional blunting can occur in children, especially with higher doses or prolonged use. Therefore, diazepam is generally reserved for short-term or intermittent use in pediatric rehabilitation. Long-term therapy may be considered only when the functional benefits clearly outweigh the risks, and when other interventions have been insufficient. Speech-language pathologists working with pediatric patients on diazepam must be aware of attention variability, fatigue, and response timing, adapting their therapeutic methods accordingly.

In geriatric care, diazepam use requires even more caution. Age-related reductions in hepatic metabolism, renal clearance, and plasma protein binding can lead to prolonged drug accumulation. This increases the risk of oversedation, confusion, impaired balance, and falls. As a result, diazepam is typically avoided as a first-line agent in elderly patients unless no safer alternatives are available. When used, it should be prescribed at lower doses, for the shortest duration possible, and with regular reassessment.

Despite these challenges, there are select geriatric scenarios where diazepam offers meaningful benefits—particularly in palliative care, terminal agitation, or when anxiety interferes with therapy adherence. In patients with coexisting neurological and psychological symptoms, diazepam may contribute to improved comfort, reduced distress, and better cooperation with rehabilitation routines. However, coordination between prescriber, therapist, and caregiver is essential to ensure safety and maintain functional goals.

Diazepam, like all benzodiazepines, carries certain risks that must be considered in any treatment plan. While generally well-tolerated when used appropriately, its side effect profile includes drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, impaired coordination, slowed reaction time, and—less commonly—confusion, blurred vision, or changes in mood. These effects are dose-dependent and more likely to occur at the beginning of therapy or when dosage is increased rapidly.

One of the most clinically relevant concerns associated with diazepam is the development of tolerance and dependence, particularly with prolonged daily use. Tolerance to the sedative and muscle-relaxant effects may develop within weeks, leading patients to seek dose increases. Psychological dependence can form even at therapeutic doses, especially in individuals with a history of substance use disorders or poorly managed anxiety. Physical dependence, on the other hand, manifests through withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt discontinuation, including insomnia, tremor, irritability, gastrointestinal discomfort, or, in rare cases, rebound seizures.

To mitigate these risks, diazepam is generally prescribed for short durations—often limited to two to four weeks for most indications. In chronic neurological conditions, where intermittent or longer use may be justified, a tapering strategy is essential when discontinuation becomes appropriate. Gradual dose reduction over weeks or months allows the central nervous system to adapt, minimizing withdrawal symptoms and preserving treatment gains. Patients must be educated in advance about the importance of not stopping the medication suddenly, even if they feel well.

In therapeutic contexts involving rehabilitation and speech therapy, sedation and attentional changes are key considerations. Excessive drowsiness may reduce therapy participation, blunt verbal output, or impair learning. Speech-language pathologists and other team members should monitor for these effects and provide feedback to prescribers about how the medication is affecting therapy dynamics. In some cases, timing adjustments—such as administering diazepam a few hours before sessions—can preserve benefits while minimizing disruption.

It is also important to consider interactions with other medications. Diazepam is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19. Co-administration with inhibitors or inducers of these enzymes can significantly alter drug levels, leading to unexpected intensification or reduction of effects. Additionally, combining diazepam with other CNS depressants such as opioids, antipsychotics, or alcohol can increase the risk of respiratory depression and cognitive impairment.

With proper dosing, ongoing monitoring, and a collaborative clinical framework, diazepam can be used safely even in complex rehabilitation scenarios. Awareness of its risks does not preclude its use—it simply calls for structured application, patient education, and individualized care planning to optimize outcomes while minimizing harm.

Diazepam holds a distinct role in collaborative care models where multiple clinical disciplines contribute to the rehabilitation of neurologically affected individuals. Its effects on muscle tone, anxiety, seizure control, and emotional reactivity make it a functional component in settings where physical, cognitive, and communicative interventions intersect. Rather than being used in isolation, diazepam is most effective when integrated into individualized treatment plans co-managed by neurologists, physiatrists, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, and behavioral specialists.

In complex rehabilitation cases, coordination between disciplines is central to therapeutic progress. A neurologist may initiate diazepam for post-stroke spasticity, while a speech-language pathologist adjusts therapy activities to align with the patient’s motor responsiveness under medication. Physical therapists may schedule sessions to coincide with the drug’s peak action, optimizing flexibility and participation. This timing-based synchronization enhances session productivity and prevents overlap between sedation periods and cognitively demanding tasks.

Within speech-language rehabilitation, particularly in cases of dysarthria, apraxia of speech, or neurogenic stuttering, diazepam can serve as a short-term adjunct that reduces motor tension and emotional lability. The therapist can use this window to introduce structured speech exercises that would be less effective under conditions of heightened muscle tone or anxiety. The goal is not to depend on the medication, but to create temporary physiological access to articulatory patterns that the brain is working to re-establish.

Emotional regulation is another area where diazepam supports team-based care. Patients recovering from traumatic brain injuries, strokes, or progressive neurological disorders often experience mood instability, frustration, or behavioral withdrawal. Low-dose diazepam may ease these barriers temporarily, facilitating trust and compliance with therapeutic routines. When this emotional scaffolding is paired with consistent behavioral guidance and functional goal-setting, patients often make more efficient progress across all disciplines.

Clinical meetings and progress evaluations provide a framework for refining medication strategies. Input from each team member helps determine whether the medication is enhancing or interfering with target outcomes. If attention span or initiation decreases, adjustments to dose timing or frequency can be made. Conversely, if the patient demonstrates better motor control or reduced resistance during exercises, the team may consider periodic use around high-priority sessions. Such responsiveness allows the medication to remain supportive rather than disruptive.

Educational outreach to caregivers and families also contributes to responsible integration. Explaining the intended function of diazepam in therapy contexts helps manage expectations and reinforces adherence. When families understand why a specific timing schedule is followed or why a dose is paused on certain days, they become effective collaborators in the recovery process. This shared understanding strengthens the therapeutic environment and helps reinforce routines outside of structured sessions.

Diazepam is not a primary rehabilitative agent, but when used selectively and collaboratively, it amplifies the impact of other interventions. Its contribution lies in the margins—in those moments where muscle relaxation, reduced reactivity, or short-term calm create the space for movement, speech, or cognition to re-emerge. With appropriate monitoring and open communication across the clinical team, diazepam becomes a flexible element in rehabilitation planning, responsive to both progress and setback, and grounded in a unified vision of functional recovery.